These past months have been a school for me and, I am sure, for many others. I am (re)learning how to wash my hands, how a virus spreads, what it means to live and work and play in the same spaces, how to navigate a barrage of (changing) information, how to host an online meeting, and probably most importantly, how much I can do without. I am also learning that systemic oppression and violence toward indigenous people and people of colour, a poisonous seed that European colonists planted in North America, has not been rooted out as many believe, but continues to grow and spread in our supposedly enlightened societies. I ask myself: how could we be so blind and apathetic to the blatant bias and brutality our neighbours experience on a daily basis?

We have no one to blame but ourselves. Let me rephrase that. We white folks have no one to blame but ourselves. However, we are slow to do just that. Our first instincts are to avoid responsibility, shift blame, and change the topic. No one likes to be the bad guy, I get that, but right now we are being invited to face some hard truths and learn some humility. Are we willing to enrol in that school? To take on the role of the student instead of assuming we know it all? To drop the paternalism and become like children? To be corrected over and over again as we listen to the witness of those whose experiences contradict our own? To recognize that some have suffered abuse and endured pain while we have been offered opportunity and comfort? At the same time? In the same place?

Humility is not fun. Neither is it comfortable. But if we believe life should be mostly fun and comfortable, we have believed a lie. Humility is necessary if we are to mature as people, especially as followers of Christ. Humility must become our constant companion if we want to walk in the way of Jesus. Read Matthew 5 - 7 again if you have any doubts. Unfortunately, Western society is not set up to teach us white folk the value of humility. Instead, we are fed a daily diet of how we can be successful, how we can beat the competition, and how we can change our circumstances to get what we want. None of this is the way of Jesus. And it saddens me to say that the Church does not have a good track record of resisting the pull of self-absorption and self-importance.

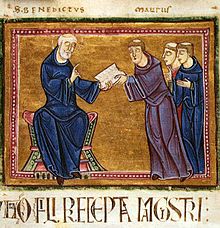

This past month, I have been reading a book which explores the twelve steps of humility found in chapter 7 of the Rule of Benedict. [1] The Rule was written around 530 CE, so to modern ears trained to hear mostly positive reinforcement, Benedict's language sounds harsh: fear the Lord, love not your own will, submit to your overseer, endure difficulties, confess sinful thoughts to the overseer, be content with menial treatment, believe you are inferior to others, do only those things endorsed by the community, remain silent, speak gently and without laughter, and manifest humility in your bearing.

How do we receive these words meant to instruct followers of Christ in humility? Do we find ourselves getting defensive because they chip away at what we perceive to be our rights, our independence, our self-expression, even our self-worth? Do we resist their corrective, restrictive tone? Do we think that we are more informed, more open-minded, more progressive than primitive 6th-century monks? If so, we could probably use a lesson or two in humility. We could start by wondering why these words seem so foreign and difficult for us. We could then let our hearts be pierced by how far removed we are from the practices of humility. We could listen and invite the Spirit to convict us of our arrogance and self-interest. Hopefully, we could begin to admit the ways in which we are blind to our own presumption of superiority.

Joan Chittister notes that "Benedict's chapter on humility, written in a period of decline and transition in Rome, was written for Roman males in a society that had always privileged Roman males. Benedict saw arrogance and narcissism at the centre of the empire and he discounted both. Instead, he began his work of spiritual renewal by making humility the very heart of his spirituality. The kind of greatness Benedict offered was the greatness at the heart of the Gospel. It was a life dedicated to God, to growth, to peace, and to community rather than to the aggrandizement of the self." [2]

Benedict's strong words were written to the privileged, to those who moved through the world with the assumption that they belonged, that they were to be respected, that they had inalienable rights, that the authorities were there to protect them, and that they would have access to the best education and housing and jobs. His words were written to people like us. They were meant to challenge habits steeped in self-reliance and self-importance. They were meant to disorient in order to reorient. They were meant as invitations to die to self. Jesus told his disciples that "unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies, it can only be a single seed. But if it dies, it bears much fruit." (John 12:24, CEB)

Humility is the pathway to inner freedom and flourishing. I like that sentence, especially the last bit. I like where humility leads us, but I tend to baulk at the steps to get there. Surely I am not expected to follow Benedict's directives to be content with menial treatment, believe I am inferior to others, and do only those things endorsed by the community. Those instructions were written for monks; surely they don't apply to us. Or do they? Our unwillingness to consider what wisdom Benedict might offer us today might be another indication that we are skipping out of the classroom of humility. And our dismissal of Benedict's insights might also reflect a general unwillingness to listen and assign value to those whose experiences are different from our own. Benedict begins his Rule with the words, "Listen carefully." This is how we enter the school of humility.

Richard Rohr writes about five messages common to cultural initiation rites, rites which are meant to move persons, especially young males, from being "self-referential boys" to become "generative, compassionate adults." [3] They are difficult truths which, for the most part, are no longer taught, especially to those whom society privileges. But, like Benedict's Rule, they are invitations to learn a different way, a humble way. They are lessons in the school of humility.

1. Life is hard. Many of us have become so accustomed to comfort, ease, and convenience that we are surprised and dismayed when life is hard and we suffer. Jesus, an oppressed brown person, was never surprised by suffering. He did not try to escape the pain of human existence but entered into it with dignity and grace.

2. You are not important. This does not mean that we are not valued and precious human beings who carry the image of God, but that the world does not revolve around us. We are but one person in the universe. Our culture teaches us to overestimate our own importance. Jesus teaches us to take the seat of least importance, to humble ourselves instead of assuming we should be exalted (Luke 14).

3. Your life is not about you. It is very difficult to decentre the self, but this is what maturity is all about. Rohr states: "Life is not about you; you are about life." Jesus invites us to deny the self in order to experience abundant life. This means we stop looking out mostly for ourselves and become connected to and concerned about the larger community. It means we learn contentment in serving instead of expecting to be served.

4. You are not in control. I have spent much of my life trying to make things happen the way I want them to, but it is a losing battle. Like love, humility never seeks to control or get its own way. Jesus taught us this when, agonizing over his impending torture and death, he prayed: "Yet not as I will, but as you will" (Matt. 26:39).

5. You are going to die. Our culture is obsessed with youth, beauty, and strength. We are taught to avoid death or anything to do with ageing. Jesus talked a lot about death to his disciples. Instead of running away from it, he turned his face toward it. He prepared for it. He confronted it. He underwent a ritual (baptism) which symbolises death as a way to enter new life. He instated a feast which commemorates his death (the Eucharist). Those who are humble learn how to die before they die. They daily die to the ego, to self-importance, to self-will, and to self-centredness.

I believe that the invitation to enrol in the school of humility is being extended to many of us during these unsettling times. Benedict, Chittister, and Rohr have outlined a few ways in which we can begin. Humility is an uncomfortable journey (again, Jesus shows us the way). It will stretch us to our limits. It will cause us pain, but it will also set us free from smallmindedness, false bravado, the need to be right, and the pressure to impress. Along the way, it will bring us great joy and peace as well. When we encounter tough times in the school of humility, our first impulse might be to run the other way, to go back to what we know, to retreat to our comfort zone, to the way things were before the pandemic and the protests championing the value of Black lives and the polarizing rifts in families and churches and communities and cities and countries about sexuality, ways to interpret the Bible, political power, and the economy. But there is no way back. We are here, now, in this moment. Do we demand the seat of importance or take the lowest place?

"Humility is the virtue of liberation from the tyranny of the self. ... The humble, no matter how great, do not spend their lives intent on controlling the rest of their tiny little worlds. On the contrary. Once we learn to let God be God, once we accept the fact that the will of God is greater, broader, deeper, more loving than our own, we are content to learn from others. We begin to see everyone around us as a lesson in living. We find ourselves stretched to honor the gifts of others as well as the value of our own." [4]

Time for school.

--------------

[1] Joan Chittister, Radical Spirit (New York: Convergent Books, 2017).

[2] Chittister, 128.

[3] Richard Rohr, "The Patterns That are Always True," March 29, 2020. Daily Meditation.

https://cac.org/the-patterns-that-are-always-true-2020-03-29/

[4] Chittister, 49-50.

Image: Rule of St. Benedict. From wikipedia.org.

Comments