In hindsight, I realise that I was taught a very high Christology, which means that the person of Jesus is viewed through his divinity (from above). As a result, the humanity of Jesus is downplayed a great deal. In my early Christian formation, the idea that Jesus might have disobeyed his parents was never considered. The thought that Jesus might have exhibited the prejudicial biases of his culture and time was akin to blasphemy. Jesus was perfect, so every action and word of his had to be perfect as well.

This concept of perfection misrepresents what the New Testament actually says about Jesus. The word translated as "perfect" is teleios and refers to wholeness, completeness, or being fully realized. It has less to do with flawlessness and more to do with being fully grown or fulfilling a good purpose. The problem is this: ideas of perfection that focus on being without fault or error negate pretty much the entire human enterprise of learning. If Jesus was truly human, not just pretending to be human (that would be the heresy of Docetism), then he spent much of life learning, especially the first few years.

He learned how to eat solid food, how to talk, how to poop on the potty, and how to walk. This meant that he also dropped food on the floor, said words incorrectly, pooped his pants, and lost his balance. Because that's what children do. He also had to learn how to share, how to follow his parents' direction, and how to say I'm sorry. Because he wasn't born knowing how to do those things. No human is. He would have learned something about geography and mathematics and literature and politics and religion, because his brain didn't come preloaded with that information. He would have made childhood friends. They would have played together and sometimes fought. He would have learned practical skills like carpentry and made a bunch of bad cuts before he learned to make mostly good ones. He would have dropped eggs and spilled milk and forgot where he put his tunic. And he would have learned what it means to be loved and what it means to be despised.

If we dismiss or erase the learning curve from the life of Jesus, we end up with some bad theology regarding the nature of God and how God interacts with humans. We can also end up with a reductionist view of change and transformation, preferring supernatural interventions and reversals, divine shortcuts if you will, over walking the long, difficult road to maturity with Jesus and his disciples. There is no shortcut to learning humility, compassion, love, peacemaking, or wisdom. The Jesus way demands that we become students and followers, not dispensers of certainty.

Little is written about the first thirty years of Jesus's life, perhaps because not much about that time was extraordinary. In all likelihood, Jesus was simply learning how to be a good Jewish boy. A story in Matthew 13 hints at this. Shortly after Jesus began his ministry, he returned to his hometown and was teaching in the synagogue. People were amazed, but not in a good way. They said: "Where did this man get this wisdom and these miraculous powers? Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Isn’t his mother’s name Mary, and aren’t his brothers James, Joseph, Simon and Judas? Aren’t all his sisters with us? Where then did this man get all these things?" (Matthew 13:54-57, NIV). The text indicates that they took offense at Jesus. Why? Perhaps because they viewed him as just one of the regular kids in the neighbourhood and now he was acting like he knew better than the religious leaders. Who did he think he was?

Over the centuries, many Christians have adopted an idealized notion of Jesus, seeing him as an exceptional, intelligent, attractive boy/man with extraordinary charisma and perfectly kempt hair. His relatives and neighbours had no such illusions.

With this in mind, let us consider two narratives from the life of Jesus. How do these stories read if we do not assume that Jesus was the epitome of human perfection from the moment he was born? What if Jesus shows us a God who enters into the human experience fully, embracing all the learning that comes with that?

We find the first story in Luke 2. Jesus is twelve years old, in Jerusalem with his family for their annual pilgrimage. He is still considered a child (thirteen being the age of maturity for Jewish males), so it is remarkable that he decides to extend his stay in Jerusalem without consulting his parents. It takes Mary and Joseph three days until they finally locate their son in the temple, sitting in on a discussion with the religious teachers. Understandably, they are almost out of their minds (ekplesso). Mary confronts Jesus: "Why did you treat us this way? We were tormented and distressed looking for you!" Jesus replies rather precociously: "Why were you looking for me? Didn't you know I would have to be in my Father's house?" His parents cannot comprehend his answer. Why would he dismiss their pain and worry like that? Why would he fail to acknowledge that he should have consulted with them before going off on his own? The rest of the conversation is not recorded, but the actions that follow speak for themselves. Jesus leaves the temple and goes home with his parents, once again submitting to them, listening to them, and coming under their guidance. In other words, he repents (metanoia) and changes his behaviour. He learns something about how to honour his parents.

The second story is found in Mark 7. Jesus and his followers are in Tyre, a busy and prosperous port city away from Galilee. A Greek woman tracks Jesus down and asks him to heal her daughter. Jesus responds with a rather harsh answer, indicating that children should receive bread before it is fed to the family dogs (meaning that the good news of the kingdom of heaven was first for the Jews). The woman persists, replying that even the dogs under the table may eat the crumbs which fall from the children’s meal. Jesus commends her for this answer and heals her daughter.

This idea of Jesus learning things from others can seem strange to us, especially if we have been told that God is immutable, immortal, and impassible. However, in Jesus we see that the divine is indeed capable of changing and growing, of suffering and being moved by the plight of others, and even dying. And this is not a new development. In the Hebrew Bible, we see a God who is steadfast in love and faithfulness (Malachi 3:6) but also known for changing pronouncements of judgment into occasions for mercy (Jonah 4:2, Joel 2:13-14). We have a God who cries out like a woman in labour (Isaiah 42:14) and delights, rejoices, and sings over beloved ones (Zeph. 3:17). This God is like a rock, yes (Deut. 32:4), but also compared to a nursing mother (Is. 49:15). YHWH is a God who enters into negotiations, seeking common ground with Moses (Exodus 32), Abraham (Genesis 18), and Hezekiah (2 Kings 20). This is not an intransigent God, but a God moved by compassion, responsive to the plight of the other.

So what does it mean to see Jesus as a learning person? Does it diminish his divinity? Not at all. Instead, it heightens the astonishing, loving, and scandalous nature of the incarnation. Does it call into question his words and actions? No, it simply puts them into perspective. Instead of a God pretending to be human, we have a God who actually IS human, a God who fully identifies with the human condition. Here is a God whose "with-ness" extends beyond teaching truths and performing miracles and enacting salvation (which are divine functions) to include the humbling and creative human vocation of learning and maturing. It frees us from the pressure to be perfect (flawless) and to get (do) everything right. It replaces the need for certainty with an invitation to explore the landscape of faith, hope, and love as devoted learners, students, and disciples. When we see Jesus as a learning person, it means that we are never alone as we stumble toward wholeness and maturity. Jesus is our companion and guide on the learning journey.

--------------

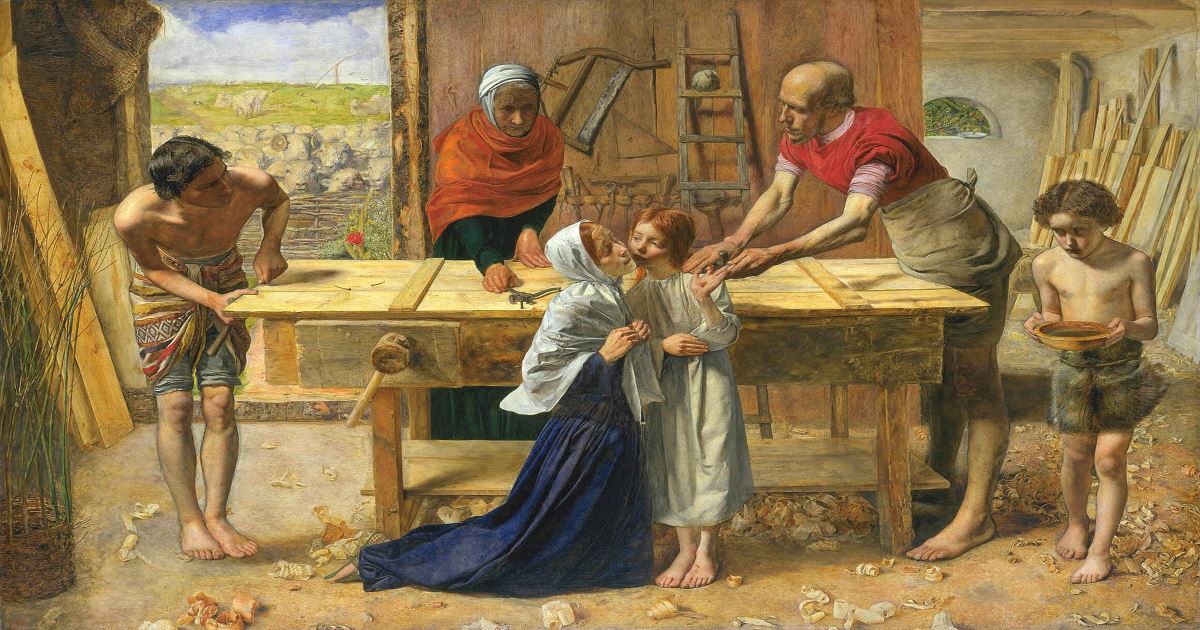

Image: Christ in the House of His Parents (1849-50) by John Everett Millais.

Comments