I have been re-reading some of the most violent books of the Bible. In Judges, we have stories of mutilation, mass murder, war, assassination, stabbing, familicide, crushed skulls, human sacrifice, gang rape, dismemberment, slavery, and abduction. It is not a pleasant read by any means. Surprisingly, some of these brutal stories have made their way into the Sunday School curriculum. The story of Gideon and his mighty men (found in the book of Joshua) is told as a lesson in relying on God's strength, not on human might. The Sunday School version highlights marching around the city, using torches and horns to disorient the enemy, but downplays Gideon rousing an army to kill men and women, old and young, cattle and sheep, and burn down the entire town (except for Rahab and her family). The story of Samson and Delilah is often told as an illustration of God giving superhuman strength to a man in order to accomplish divine purposes. Sometimes it is also framed as a tale of warning against being seduced by the enemy (and/or women). In the end, God's strength returns to the wayward Samson so that he can kill more people with one action than all his previous violent actions put together. The whole narrative is disturbing in many ways. And these are but two of the grisly, troubling stories we find scattered throughout the history of Israel.

Finding the wisdom of God in these stories is a challenge. When we have a whole collection of them, like the brutal book of Judges, it makes one wonder: what are the lessons to be learned here? Are we to wipe out our enemies without mercy? Are we never to marry outside our cultural group? Are we to sacrifice a member of our family just because we made a thoughtless vow to God? Are we to incite a civil war in order to revenge the murder of one person? In light of the whole witness of scripture, I would say the answer to all of the above is no.

So, what exactly is the purpose of the book of Judges? Biblical scholar, Robert Alter, suggests that the narratives found here do not give us patterns to follow but offer a critique. Alter states that the intentional and cohesive purpose of these stories is to trace "the breakdown of the whole system of charismatic leadership." [1] The leaders are charismatic in the sense that they gain authority not through being chosen by the people or inheriting their role, but by some charism (gift). The judges or chieftains are mostly ad hoc military leaders who have some form of encounter with the spirit of the Lord by which he or she "is filled with a sense of power and urgency that is recognized by those around him [her], who thus become his [her] followers." [2]

The failure of this system of governance is laid out in chapter 2: "And then the Lord raised up judges for them [Israel], the Lord was with the judge and rescued them from the hand of their enemies all the days of the judge, for the Lord felt regret for their groaning because of their oppressors and their harassers. And it happened, when the judge died, they went back and acted more ruinously than their fathers, to go after other gods, to serve them, to bow to them. They left off nothing of their actions and their stubborn way." (Judges 2:16-20) Alter nicknames Judges "the Wild West era of the biblical story" and this description captures the dangerous, violent, lawless, "take what you can get," "every person for themselves," tone of the stories which recount the downward spiral of Israel and Israel's leadership. [3]

As one brought up with a high view of the Bible, I know firsthand the tendency to make heroes and saints out of biblical characters and downplay their imperfections, mistakes, and harmful actions. When we read these troubling stories as hagiographies, we become blind to the critiques and warnings embedded in the texts. Samson and David may be heroic in some ways, but their actions born out of revenge, lust, and self-interest are as instructive as their mighty deeds.

Some read the chaos of Judges as a set-up for the coming monarchy, and to some extent, it does do that. However, these are not merely tales about an adequate (though imperfect) system of leadership giving way to a better system. The judges are not a foil to the ultimate hero-king, David. No, these stories mean to train us in recognizing the various pitfalls of leadership so that when we finally come to the story of David, we are not dazzled by his military prowess or his good looks or his charisma; we can see both the man after God's heart as well as the cruel, sly mercenary. Even Samuel had a hard time looking beyond outward appearances (1 Sam. 10:24; 1 Sam 16:1-13). That a prophet of God, a seer, has trouble seeing rightly, is a bit of irony meant to alert the hearer/reader that the characters and storylines are complex: everyone is on a learning curve, anointed leaders get some things right and some things wrong, very little happens without some form of struggle, people lead from weakness as much as strength, and very few characters are wholly good or wholly evil.

Troubling stories invite the reader to engage with the text deeply, to ponder the meaning, to wrestle with the inconsistencies, and to resist looking for easy answers. There are a few principles that I have found helpful when reading challenging texts (especially violent ones) in the Bible. Perhaps they will be of use to you.

1. Remember the trajectory of the story of God.

Every story, every set of rules, every song and prophecy, every letter, every book, is but a part of the greater story. How does this particular story/text relate to earlier stories? How does it set the stage for later events? How does it harken back to the origin story focused on goodness and caretaking? How does it look forward to the appearance of God in human form: Jesus? How does it hint at the unfolding justice and mercy of God? How does it make us long for all things to be made new? If we think of the basic elements of a story or drama (anticipation, adventure, success, frustration, loss, challenge, hopelessness, transformation/learning, creative solution, resolution, celebration), where does it fit into the overall arc?

2. Look for the exceptions.

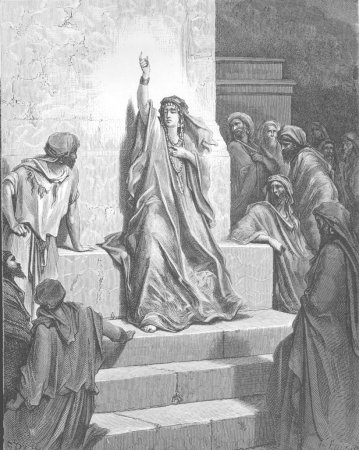

Many of the profound insights in the biblical texts come from noticing the exceptions. The life and teachings of Jesus are rife with them. There is a despised Samaritan fulfilling the law better than respected religious leaders, unlearned fishermen chosen as disciples, Jesus inviting himself to a tax collector's house, a woman evangelist, and a poor widow exemplified as a generous benefactor. In Judges, some of the exceptions are the women who influence the course of history (Deborah as judge, women dealing the death blow to evil men, Delilah saving her family from death), a left-handed warrior (probably considered unclean), a chieftain who was the son of a prostitute, a messenger of God who sidesteps the man and appears to his wife, etc. Noticing exceptions does require some knowledge of the culture when the text was written, so find a good commentary and dig in.

3. Read the texts in light of Jesus.

In the case of Judges, notice where these judges, warriors, and chieftains contrast or point forward to Jesus as just judge and servant king. What rituals or practices foreshadow a coming Messiah? What words or actions are echoed by Jesus in his teachings? Where do we see salvation or rescue taking place?

4. Notice recurring themes.

An oft-repeated phase in Judges is: "Isreal did evil in the sight of the Lord." This highlights the pattern of Isreal turning away from God, trouble coming their way, and God sending help. In 1 Samuel we find the story of Samuel and Saul which features a theme of seeing and not seeing. It is fascinating to trace this element throughout the narrative. Another recurring motif in the history of Israel is all the ways divisiveness creeps into what is supposed to be a unified nation. In Judges, these themes are mostly warnings, but they also offer hope for a better way forward.

5. Where is wisdom?

No one part of the biblical text carries the whole wisdom of God, so we must be careful not to read one story or one directive and make it universal. Sometimes what is inferred or stated in one text is mitigated or even contradicted in another text. This is not meant to confuse us, but to give us a fuller picture of how God interacts with the world. In some ways, our faith traditions have taught us to look for commands or laws so that we have a set rule to follow. However, the Bible does not function as a rulebook; it offers us training in wisdom. The biblical texts can help us discern what is best, right, fitting, just, loving, and the most beautiful action in a particular situation. When reading a story, ask what wisdom (not just a rule or principle) it might be offering.

6. What does it tell us about the nature of God?

Some have interpreted the stories we find in the Hebrew Bible to mean that God uses whatever means necessary to achieve a good end, even if that is murder. In light of the life and teachings of Jesus, I don't believe this is a good interpretation of these narratives. Despite (not because of) the brutal violence, YHWH bends the story toward rescue, time and time again. One would think that God would tire of forgiving and saving, but these terrible stories bear witness to the patience and longsuffering of YHWH. And yet, evil does not go unpunished. YHWH is not blind to injustice. There is consistency as well as creativity in the character of YHWH and when we read the biblical texts, we must be careful not to confuse the two. We must avoid extrapolating universal principles from particularities. Instead, look for the fruit of the Spirit of God in the text (Galatians 5). Look for faithfulness. Look for mercy. Look for justice. Look for hospitality. This is the consistent nature of God. And it shows up in so many creative ways.

Learning wisdom is hard work and it is never done. But wisdom is the gift that the scriptures offer to us: if we engage with them well, they can teach us the way of Jesus.

----------------

[1] Robert Alter, "Introduction to Judges," The Hebrew Bible, vol. 2, Prophets (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2019), 78.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid., 80.

[4] Ibid., 79.

Image: Deborah Praises Jael by Gustave Doré. Public Domain.

Comments